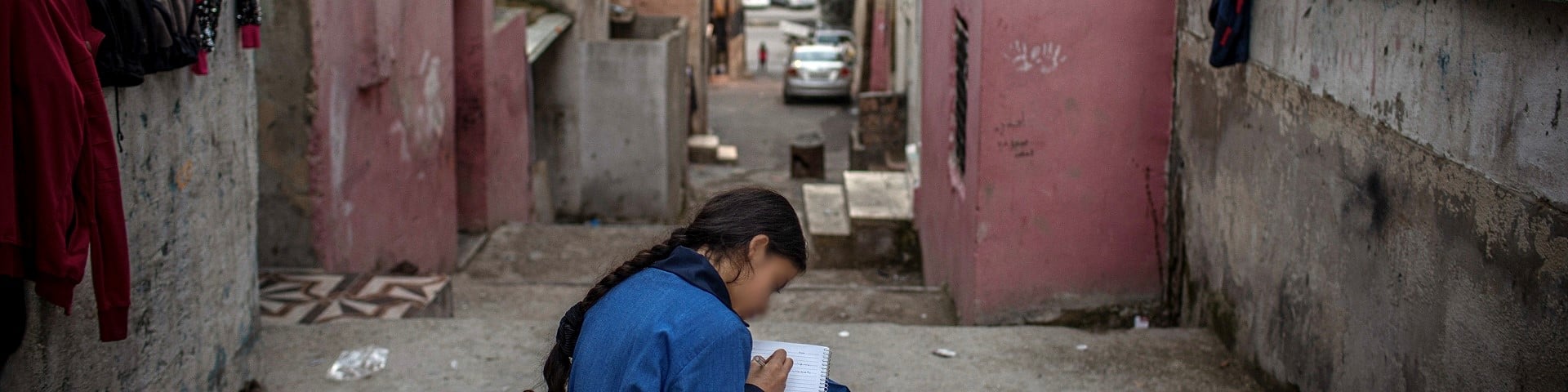

As a result of the civil war in Syria, millions of people have fled the country. The vast majority of them live in Syria’s neighbouring countries. This has put severe pressure on infrastructure, public service delivery and social relations in the host countries. The Netherlands has provided support in the areas of protection, education and employment to offer prospects to refugees and host communities. IOB evaluated Dutch support for the reception of refugees in the Syria region for the period 2016-2021.

Background

In response to the European refugee and asylum crisis in 2015, the Dutch government allocated 260 million euros to support the reception of refugees in the Syria region. Since then, reception in the region has become an important pillar of the Dutch migration policy, and the financial resources for this policy have been structurally expanded. The political arguments in the Netherlands for (financial) solidarity with host countries have varied. In addition to improving the prospects for refugees and host communities, preventing onward migration to third countries, including Europe and the Netherlands, was an important motive as well.

In line with international policy developments, the Netherlands adopted a development-oriented approach that went beyond providing traditional humanitarian types of assistance. Support was aimed at the (temporary) integration of refugees into the societies and economies of host countries to enable them to become self-reliant.

For this evaluation, IOB looked specifically at Dutch support for the reception of refugees in the region in Lebanon and Jordan (and partly in Iraq) for the period 2016-2021.

Main research question

What has been the Dutch contribution to improving the prospects of refugees from Syria and their host communities in Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, and how can this contribution be improved?

The study looked primarily at the state of affairs in Jordan and Lebanon. When possible and relevant, data from Iraq was also incorporated.

Image: © ILO/G.Megevandl; ILO/A.H.Al Nasier; Adam Patterson/Panos/DFID

Conclusions

The main conclusions are briefly presented below. First, the main conclusion is summarised. Subsequently, the other conclusions are discussed. More details can be found in the evaluation report.

Primary conclusion

Dutch support to Lebanon and Jordan has achieved positive short-term results for refugees and host communities. Examples include access to education, protection of women and children, and the ability to meet urgent daily needs through cash assistance to families. However, Dutch support has not effectively contributed to improving the prospects and self-reliance of refugees and host communities. For many, prospects have deteriorated, particularly in Lebanon. This was partly due to negative contextual trends beyond the influence of the Netherlands, such as political crises and economic decline, aggravated by Covid-19, and partly because a critical assumption underlying the policy – i.e. that host countries would be willing to adopt an inclusive approach towards refugees – did not hold in Lebanon and only partially in Jordan.

- Dutch support for protection, education and employment may have influenced refugees’ aspirations and capabilities to migrate to European countries, including the Netherlands. However, the evidence for a causal relationship is weak. The decision to migrate is determined by many factors that are difficult to predict. For most refugees in Lebanon and Jordan, onward migration remains impossible due to a lack of financial resources and networks.

- The chances of many projects contributing to the policy objectives were reduced, i.e. because of unrealistic goals or overlooked factors that were crucial for achieving (sustainable) results, such as differences in religious, cultural and social norms. The Dutch programmes were flexible in the sense that they allowed programming to adapt to important contextual changes.

- The intention to integrate the specific needs of women and girls into projects was not sufficiently successful.

- The Netherlands supported both refugees and host communities; however, the public perception remained that foreign aid benefited refugees more than the local population.

- Policy coherence was limited in various ways. The priorities of international donors, including the Netherlands, were not always aligned with those of the host countries. Donor coordination focused more on sharing information and establishing joint positions, rather than avoiding duplication and promoting synergies. In addition, the promotion of a coherent package of Dutch support was limited by the large number of Dutch instruments.

- a) The shift from a portfolio of individual projects towards a partnership with large international agencies (‘Prospects’) has facilitated contract management. Such a partnership required more staff than expected, and investments in this were made at a later stage. Cooperation between the ministry and the embassies has improved in recent years.

b) The Prospects partnership brings together key humanitarian and development partners. This has stimulated the exchange of information between them, but it remains a challenge to actually set up projects together.

c) The ambition to give local organisations more control over programming proved difficult, especially when working with large international organisations. These usually did not pass on to local organisations the favourable conditions they enjoyed, such as multi-annual and flexible financing.

Image: © ILO/A.H.Al Nasier; UNHCR/Sara Hoibak; ILO/Nadia Bseiso

Recommendations

Five policy recommendations are presented below. More detail regarding these recommendations can be found in the report.

- Make key policy assumptions explicit and regularly examine their validity in specific contexts, preferably with partners and local stakeholders.

- Be realistic about which goals you can achieve in volatile contexts.

- Determine beforehand how gender mainstreaming and gender equality should be prioritised and operationalised, and ensure that it is done in a meaningful way.

- Only spend newly released development funds after a sound policy approach and results framework have been developed.

- Stay committed to an active dialogue with host governments to maintain a degree of goodwill.

- Keep exploring ways to promote more inclusive approaches to refugee reception.

- Consider possible innovative pathways to increase self-reliance.

- Consider strengthening the Dutch approach to responsibility sharing, for instance by increasing the resettlement quota and making this more visible to host governments. In this way, the Netherlands can continue to recognise the host countries’ concerns and remain in dialogue.

- Try to work with local governments (municipalities), taking care to avoid potential negative unintended effects.

- Ensure that policies, programmes and interventions are based on national (and even local) contexts and needs. Also include the added value of the Netherlands.

- Develop mechanisms to involve local stakeholders and refugee representatives in all phases of programming.

- Continue to focus on preventing tensions between population groups and promoting social cohesion.

- Ensure that international organisations within the Prospects partnership involve and strengthen local organisations.

- Clarify what is expected of the partners in the area of joint action.

- Organise the partnership in such a way that other donors can join.

- Allow flexibility for other organisations to join as partners when this adds value in a particular country context.

- Invest in longer-term specialised staff by establishing appealing career paths.

- Promote inter- and intra-learning at the policy department, embassies and local partner offices.